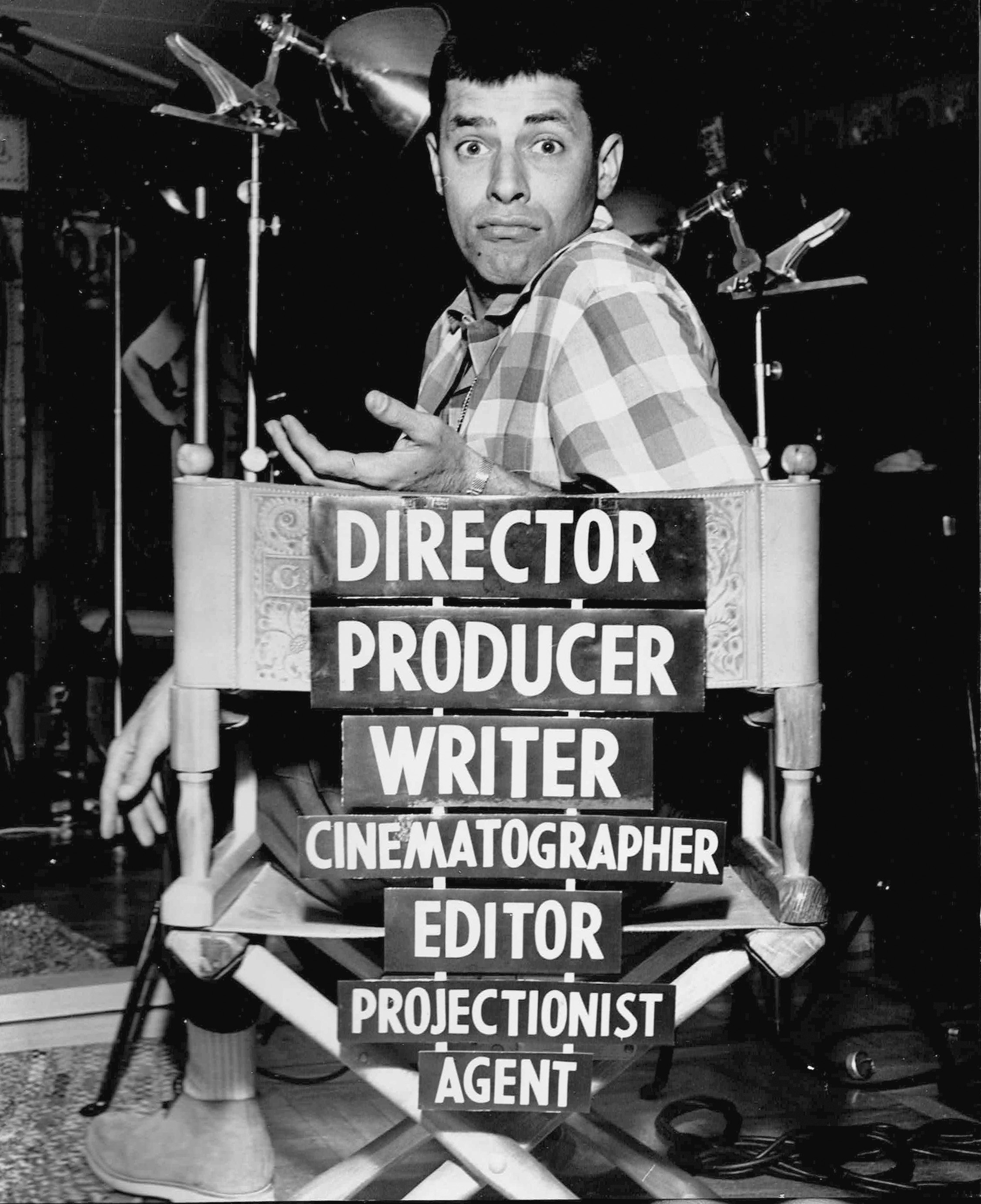

The Total FilmMaker

In the late 60’s the funniest man alive appeared weekly at the USC Film School. His now-legendary lectures, originally published as The Total Filmmaker in 1971, are available in a new reprint edition for the filmmakers, fans, and film buffs of the 2020s.

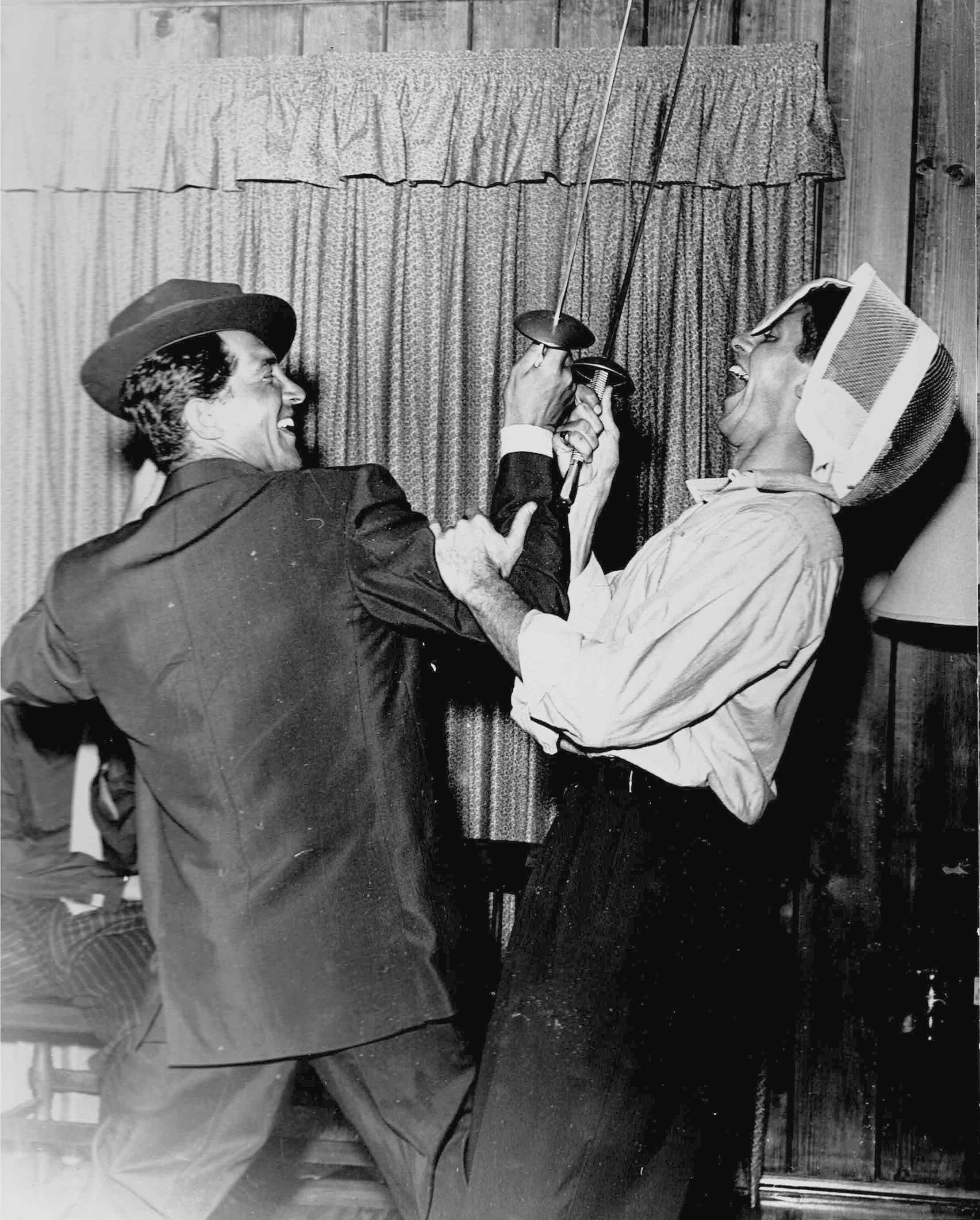

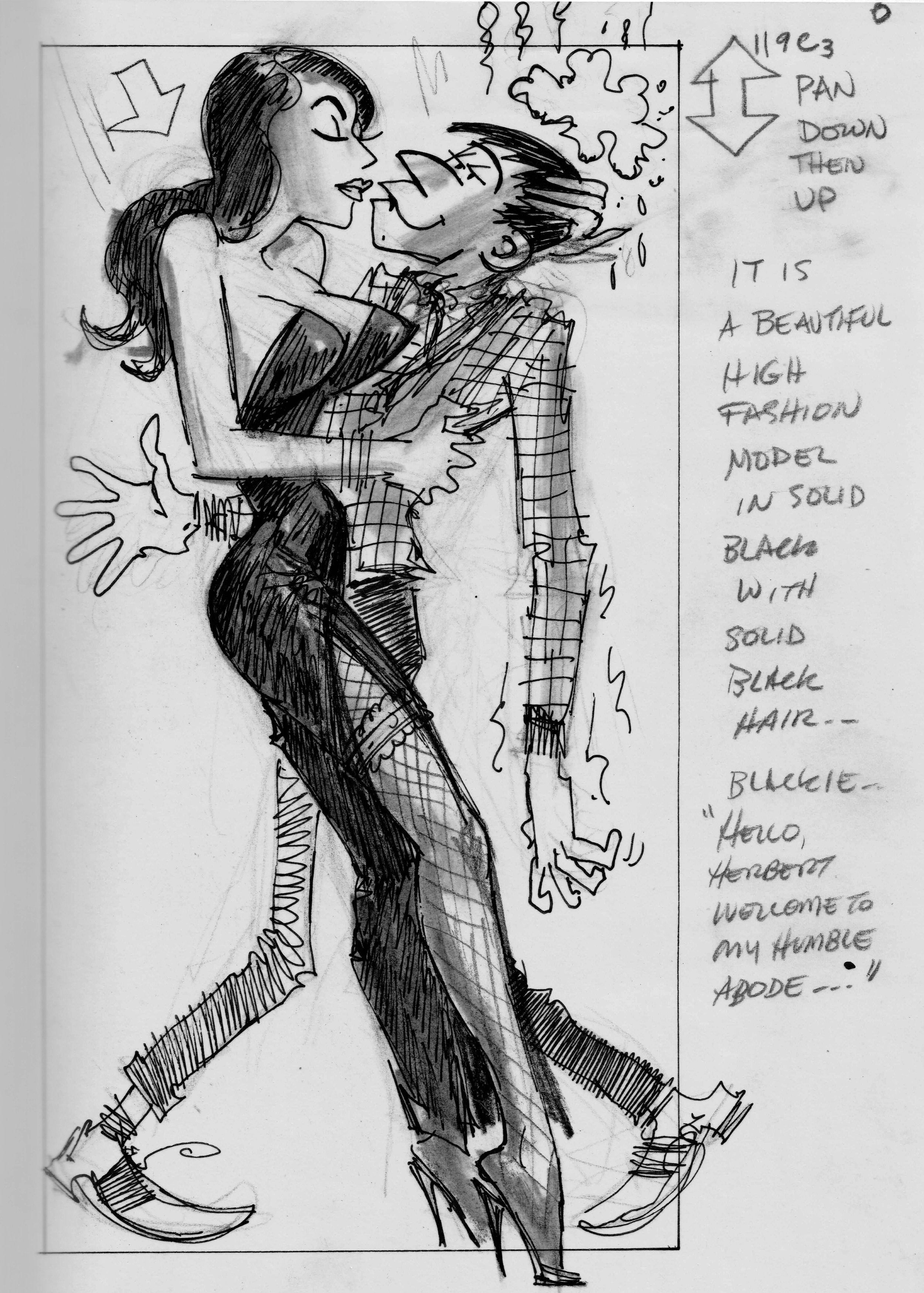

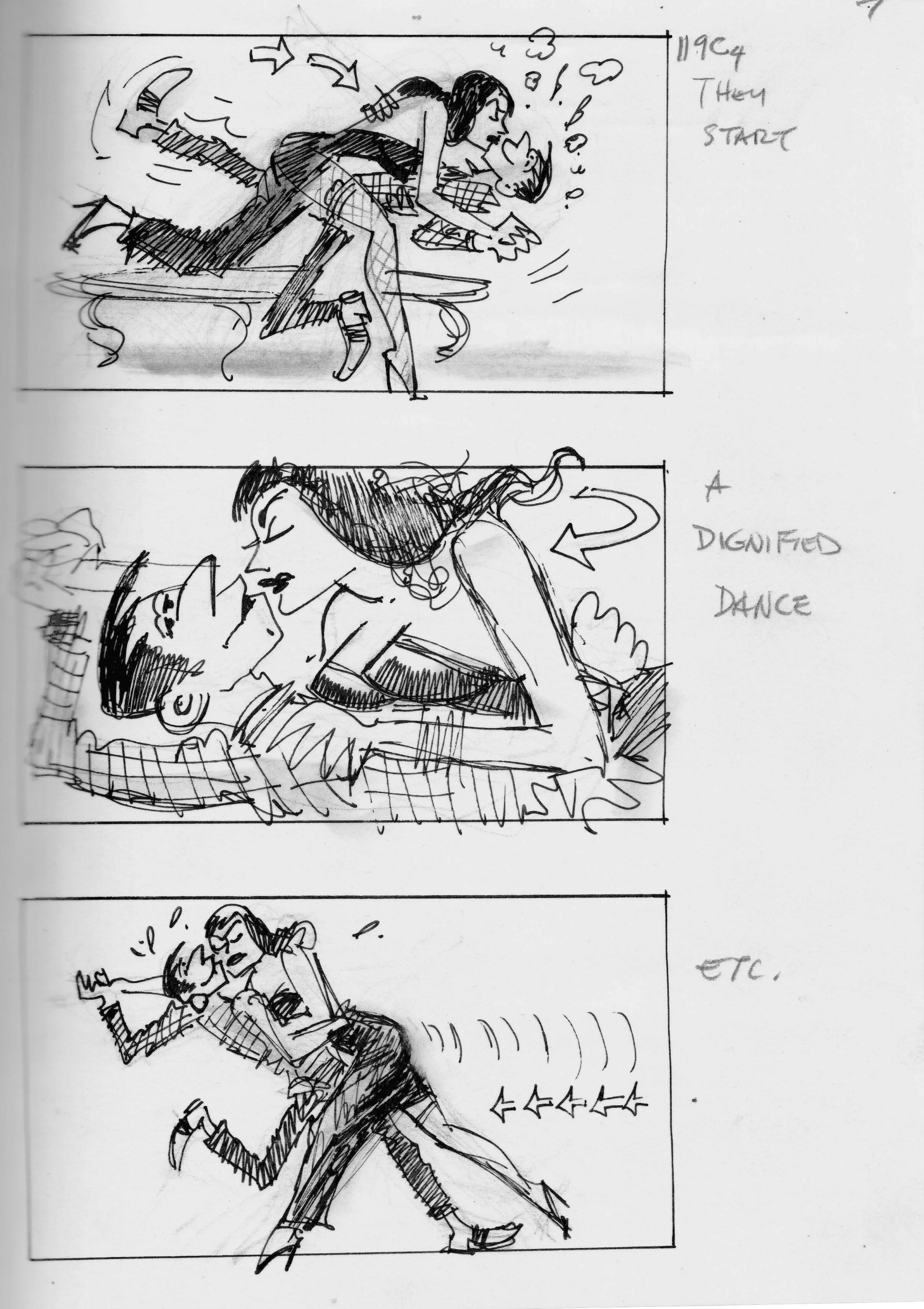

The Jerry Lewis Estate and MWP have teamed up to re-release this classic. Here is an excerpt from the book—including rarely-before-seen photos from family albums, as well as a few of Jerry’s fascinating hand-drawn storyboards.

—

Chapter 17

THE COMEDIANS

I do not know that I have a carefully thought-out theory on exactly what makes people laugh, but the premise of all comedy is a man in trouble, the little guy against the big guy. Snowballs are thrown at the man in the black top hat. They aren’t thrown at the battered old fedora. The top-hat owner is always the bank president who holds the mortgage on the house, or he’s a representation of the undertaker.

In the early days, working nightclubs, I learned that taking a pratfall in a gray suit might get a few laughs. But I had to get up quickly and start another routine. Take the same fall dressed in a $400 tuxedo, and I could stay on the floor for a minute. They would howl when the rich guy took the tumble.

Or it is the tramp, the underdog, causing the rich guy, or big guy, to fall on his ass. In this respect the sources of comedy are a simple matter of who’s doing what to whom. They include, of course, what the comedian does to himself.

Chaplin was both the shlemiel and the shlimazel. He was the guy who spilled the drinks—the shlemiel—and the guy who had the drinks spilled on him—the shlimazel. In his shadings of comedy, and they were like a rainbow, he also played a combination of shlemiel-shlimazel. In Modern Times, diving into six inches of water when he opens the back door, which is one of the great sight jokes in comedy-film history, he does it to himself.

My Idiot character plays both the shlemiel and the shlimazel, and at times the intermix. I’m always conscious of the three factors—done to, doing to self, and doing to someone else by accident or design—while playing him, but they are not in acute focus. They swim in and out at any given moment.

In studying Chaplin’s films—where he is an aggressive character, protective character, defensive character, but always the center point—an erratic pattern emerges. I think this is because of his many shadings. In Modern Times he plays both the tramp and the underdog. While both are aggressive, they are not the same characters.

The character who opened the door and dived headfirst into the mud was not the same character who was pushed by the cop. “None of that,” he said. The latter character wouldn’t have been so stupid as to dive into six inches of water. Often this type of shading is not written into the character. It is added, instinctively, by the comic.

In shadings and coloring, I think there are more demands made on the comic than on the straight dramatic actor. Although comics seldom perform straight dramatic roles, usually as a matter of choice, they have a relatively easier time in shifting to them than does the dramatic actor who is suddenly confronted with comedy. Many of the best dramatic actors lack a genuine sense of comedy know-how.

In the old days at the Palace in New York, when Eddie Cantor walked on the stage, his sweet Jewish aunt would say, “Look at my Eddie. He acts like a dummy.” And Eddie was acting. Milton Berle has done some marvelous acting roles. Jack Lemmon is a superb dramatic actor, The Days of Wine and Roses—as well as a damn good comedian.

The making of comedy is a very serious business within the dramatic structure of entertainment. On the level of pure performance, comparing comedy and drama, I think comedy is more demanding. The straight dramatic actor has his skills and emotional tools, as does the comedian. But if he wakes up on a smoggy morning, stomach lousy and head full of aches, it is not too difficult to choke to death a while later playing Hamlet. The comic finds it somewhat tougher to turn on laughter if the world is funky and smoggy.

—

Stan Laurel was probably a near genius as a comic and as an authority on what makes people laugh. He was also a total filmmaker. Toward the end of his career, after great self-schooling, he had become one of the finest technicians in Hollywood, in comedy or drama. I learned much from him, particularly in the last three or four years of his life. He was a Moviola fanatic, a camera fanatic.

—

The directors who worked with Laurel and Hardy were confined to their ground rules, especially Stan Laurel’s. Stan was the brains. Ollie was a tremendous exponent, possibly equaled only by Harold Lloyd. He could do anything with Stan when the material was given to him. They were an almost perfect comedy combination.

Stan told me that Ollie started looking into the camera, communicating directly with the audience, because he was never too sure what the next cue would be. He would take his cues from the script supervisor, who was always immediately to left or right of camera. Ollie would roll around, get his cue, and then continue. It was effective, and they kept it. Although normally a legitimate “no-no” in filmmaking, it became one of their trademarks.

Even though they had writers, and Hal Roach Studios was overrun with them in the thirties, Stan did much of the writing. There was some bit of comedic genius in each film they did, and Stan contributed many of them. His touches, such as the hat that would elevate when he leaned against the wall and blew his thumb, are evident throughout their work.

He did a classic sequence in Saps at Sea where Ollie would turn maniac if he heard horns. Placing the four or five pieces of trombone slides, timing the run around the boat with Ollie to bring him to danger at the precise moment, was a near-perfect work of comedy pace and film cutting.

Stan understood the camera and what they, as a team, were doing visually in relationship to it. Much of their material played so well in the masters that they never dreamed of trying to match it in closer shots. The matching came from straight dialogue scenes where they could make a crisscross or an over-on.

With visual slapstick content they worked loosely, because matching would have been impossible on many occasions. They moved from master head-to-toe, loose head-to-toe, to nothing more than a calf shot in some sequences. They wouldn’t take the chance of restricting themselves because of spontaneity.

No material of consequence was out of the frame in their films. There was a lot of head room and air, left and right, in most of their compositions. It gave them space for spontaneous comedy, although their material was always written and prepared.

They finished their careers almost penniless. They weren’t good businessmen and had no corporate setup. Few actors bothered about business in those pretax days. And Hal Roach had them tightly corralled, anyway. Laurel and Hardy made a lot of money but kept little of it. Stan was married seven times and was always a soft touch. Ollie was a barfly and a golf hustler. He left his dollars by the mahogany rail and on the greens.

Hardy died in 1954, and Stan was so affected by it that he had a stroke that same morning. After that day, Stan was paralyzed and seldom went out again. He couldn’t bear the thought of anyone seeing him in that condition. He told me, “Better they have the memory of fun.” He stayed in his Santa Monica apartment from 1955 until his death in 1965.

Critical acceptance came late for Laurel and Hardy. It is one of the crueler stories of this put-on we’re living in. The critics and the jet set seldom recognize something in motion. They wait until it is static or buried before they slowly creep out into the night to discover that once upon a time the masses enjoyed it. When recognition comes, the masses are busy enjoying a new, active thing.

—

I’ll admit I can’t wait to hear what is said about me after I croak. Being a part of the put-on, I’ll also admit I’d like to go somewhere now to hear it.

—

Jack Benny is the best in the world at what he does, yet he is not a film comedian. His comedy is not for the visual medium in theaters for the world market. He can do TV specials that are very funny to an English-speaking audience, but they don’t dig Benny in Rome. They do not understand buying one gallon of Texaco gas.

And any foreigner would have trouble really appreciating Bob Hope at his best. Hope has little competition at stand-up comedy. He makes no bones about the fact that his material is written for him, but no one else can put it across like Hope. The beauty of his talent is that he knows his limitations. His cream is monologue, and he stays in that confine. He can’t do a monologue on TV for sixty minutes, so he hits them for twelve and then goes into a sketch. Hope does films but depends on his character more than visuals.

Lenny Bruce was the most infuriating man I ever met in my life because he preferred to make his way with four-letter words. He was brilliant but couldn’t make it as a straight comic. So he steered that brilliant mind into a joint with fifty-eight people. He could have swung with the best if he’d gone straight. I am not the enemy of Lenny Bruce, rest his soul, or the enemy of Mort Sahl. I am angry for them, not against them. I am angry with Andy Warhol for the same reason—wasting talent on so few, rather than working for the masses.

Harold Lloyd never touched my soul because nothing appeared to affect him, and I’ve never been able to include him in the category of great comedians. He was a great technical comic.

The great ones, the giants, are Chaplin, Stan Laurel, and Jackie Gleason, in that order.

Excerpt taken from the newly-released edition of The Total FilmMaker